Animating Text Art in JavaScript

It is with no small thanks to MDN, StackOverflow, Firefox's support for countless open tabs, JavaScript's support for first-class functions, and first-class supportive colleagues, I learned it is possible for a web front end novice to program "text art animations". Whatever that is even. Because I thoroughly enjoyed doing just that for Hanukkah of Data 2022. Here's how it went down.

Contents

"Data Puzzles in December"

A perfectly innocent-looking thread saulpw (a.k.a. Saul Pwanson) started in the Recurse Center community Zulip. Tame enough to scroll past at first glance. As did I. Lucky me, someone did not. "What's a data puzzle?", they asked.

So. Saul wanted to create an AoC-like 1 for data nerds 2. He elaborated thusly:

"… they're puzzles that you solve from the data clues.

Like here's one: You overhear someone saying that they're in "the only place in the state where you can join the mile-high club in a church". And you would get a list of US places and figure out which place it must be."

— saulpw

Long story short 3, there I was, tagging along with a merry band of Devottys and assorted gentlenerds, tryna make a thing.

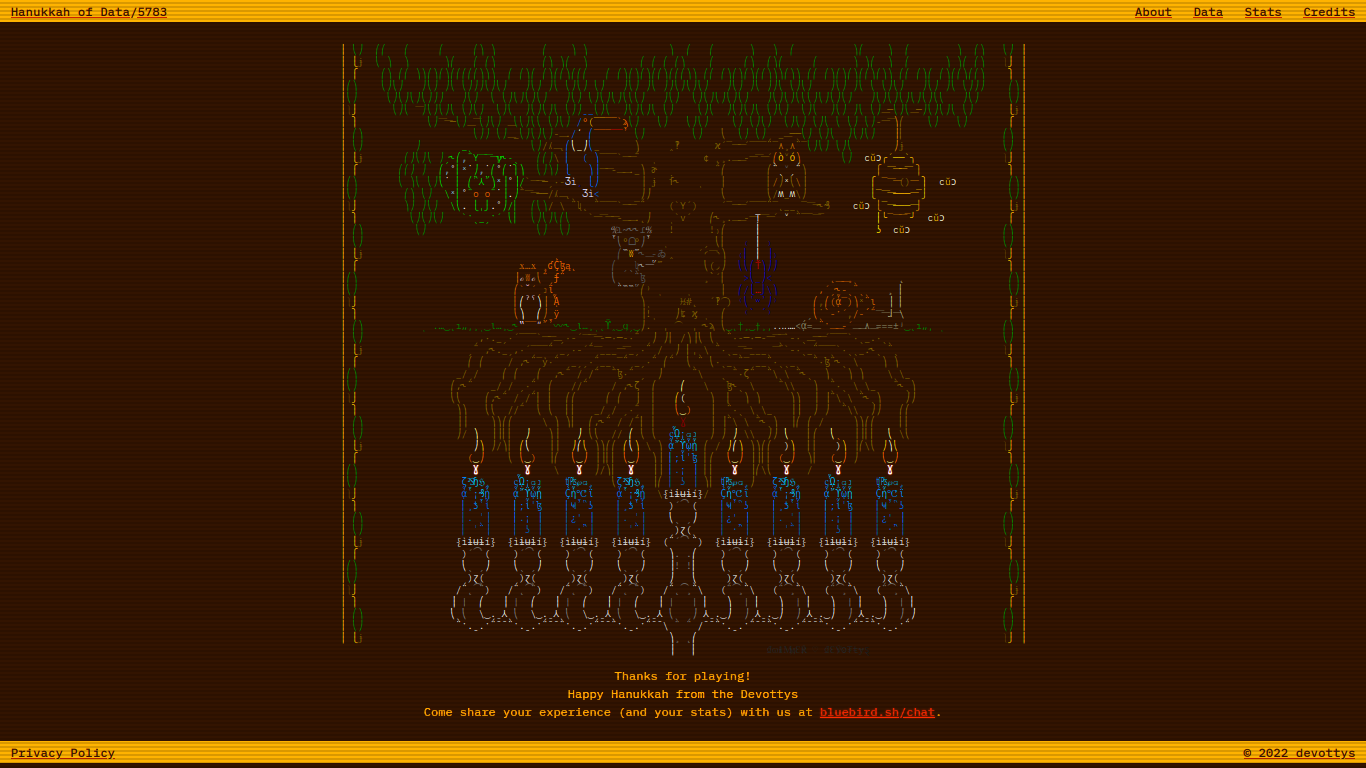

The goal became to create a local-first game experience. Where the puzzle data set is a file to download (CSV, JSON, SQLITE). Each day, a puzzle question is released to the website. There is no central scoreboard. Stats are personal. Answers are validated locally. Correct answers beget lightings of flames, reveals of parts of a tapestry, complete with animated animals.

Oh yes, Animated Text Art!

What is Text Art Animation even?

'tis Pointillism in motion. Imagination cast as pure data. Digital art with, ah, character.

⎠( ⎠/⎞⎜ ⎠⎞ ⎟⎟ ⎛( ⎞⎞⎛⎛ ⎠⎛⎞ \ ⎞ ᾆ῎ϔᾧᾗ ⎛ / ⎛⎝ ⎞⎞⎛⎛ ⎠⎛⎝ ⎜⎜ ⎛⎛⎝

⎝‿) ⎝ (‿⎠ ⎟⎛ ⎝‿) ⎟⎟⎜⎜ ⎝‿⎠ ⎞⎟ ⎜;ἷˈɮ ⎜⎛ ⎝‿) ⎟⎟⎜⎜ ⎝‿⎠ ⎞⎜ ⎝‿⎠

Ɣ Ɣ \ Ɣ ⎠/⎞⎜ Ɣ ⎟⎟ ⎜.¡ ⎟ ⎜⎜ Ɣ ⎟⎛\⎝ Ɣ / Ɣ

ζ⅋ɧℌ¸ ҁᾯ¡ҩℷ ʧ₧℘ҩ¸ ⎝ζ⅋ɧℌ¸ ⎟⎛ ⎜ ʖ ⎟ ⎞⎜ ʧ₧℘ҩ¸⎠ ζ⅋ɧℌ¸ ҁᾯ¡ҩ

ᾆ῟¡₰ᾗ ᾆ῎ϔᾧᾗ Ḉἧ℃'ῒ ᾆ῟¡₰ᾗ \{ìɨʉɨí}/ Ḉἧ℃'ῒ ᾆ῟¡₰ᾗ ᾆ῎ϔᾧ

⎜¸ƾ῟ἷ ⎜;ἷˈɮ ⎜Ҹ῏῝ʖ ⎜¸ƾ῟ἷ )ˊ⁀ˋ( ⎜Ҹ῏῝ʖ ⎜¸ƾ῟ἷ ⎜;ἷˈ

Lots of character in fact. Each UTF8 character chosen with care. Each instance of each character lovingly hand-picked, painstakingly hand-placed, and coloured. Animated Text Art is several frames worth of this loving, caring, painstaking arrangement of plain text. Maybe two frames that blink at you, maybe forty-two that make a candle flame dance. A craft that hearkens back to Ye Olde days of hand-drawn animation.

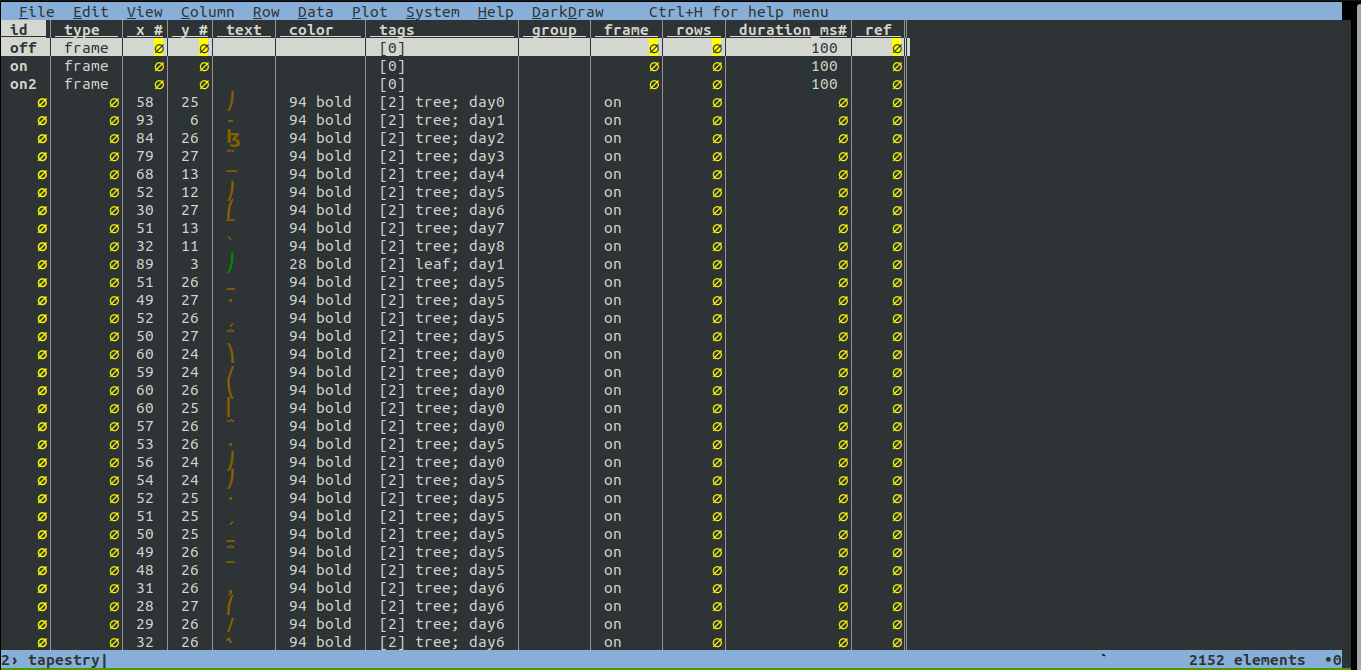

And here it is, exported as JSON:

{"id": "off", "type": "frame", "text": "", "color": "", "tags": [], "group": "", "duration_ms": 100},

{"id": "on", "type": "frame", "text": "", "color": "", "tags": [], "group": "", "duration_ms": 100},

{"x": 76, "y": 5, "text": "\u0194", "color": "88", "tags": ["wick", "day1"], "group": "", "frame": "on", "href": "1"},

{"x": 40, "y": 1, "text": "\u0194", "color": "88", "tags": ["wick", "day0"], "group": "", "frame": "on"},

{"x": 46, "y": 11, "text": "{", "color": "255 bold", "tags": ["menorah"], "group": "", "frame": "off"},

{"x": 52, "y": 11, "text": "}", "color": "255 bold", "tags": ["menorah"], "group": "", "frame": "off"}But, honestly, 'tis awesome sauce that mere pictures do not do justice to.

Go play Hanukkah of Data to uncover the art and animations for yourself! Or cheat 4.

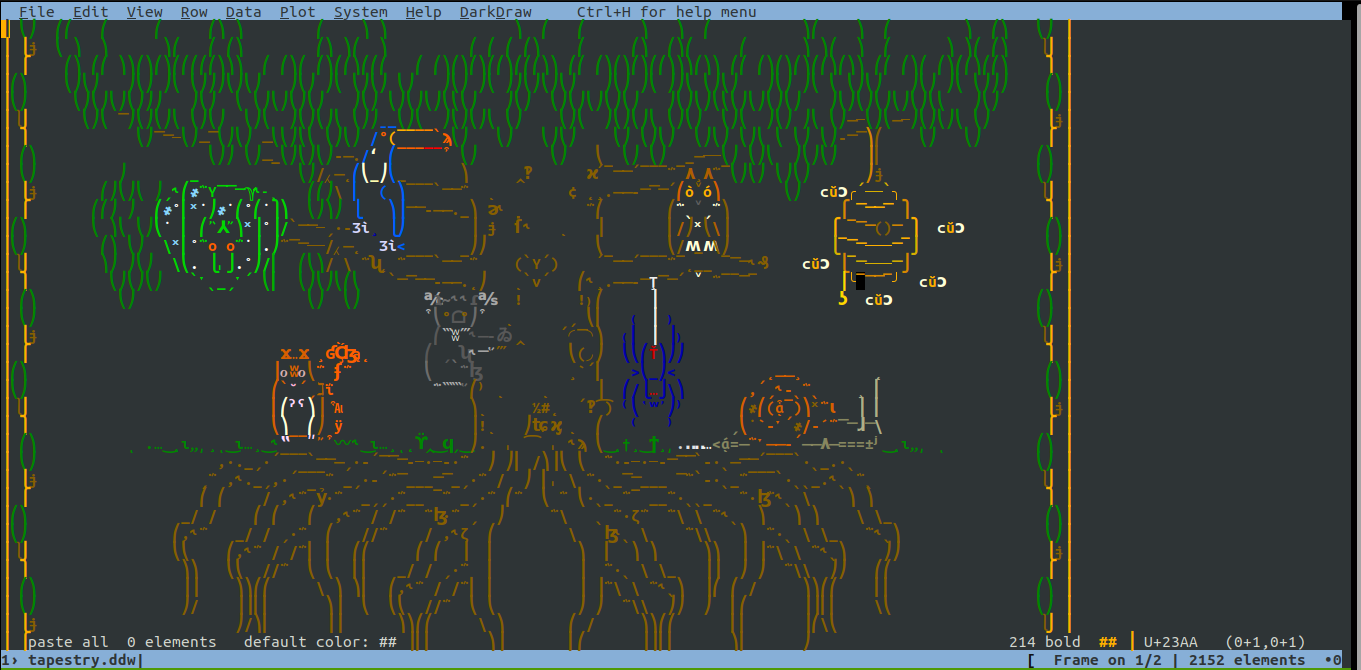

From DarkDraw to thine Browser

Text Art can literally be Javascript too, if your artist draws in DarkDraw and your build pipeline exports plain text ddw file contents straight into handy JSON arrays.

for i in menorah tapestry flame ; do

echo -n "const ${i}DDW = "

vd -b resources/${i}.ddw -o - --save-filetype json

done > assets/js/text_art_data.jsAnd this is where the front end novice—yours truly—begins to git forge ahead, footguns in both hands, pointed squarely at feet, after this fateful utterance…

"Sure, I'll try to Javascript the Text Art Animation.".

— Yours Truly

A foolish line, as I was soon to discover.

For it was a thing I had never really done. Write Javascript, I mean. The foolishness comes naturally. Luckily it was virtue this time. If I had known how much I'd sweat trying to do justice to the talented dwimmer's Text Art, I'd have quietly stayed home.

Still… I knew that Javascript is a fairly Functional language, which provided comfort that I could do something. In the end, I think it came out alright, in about 200 lines of code, warts and all.

grep --count -v -E \

-e "^$" -e "//" -e "/|\s+\*.*" \

assets/js/text_artist.js

213Architecture: Discovering the spreadsheet in the problem

Spreadsheets are a personal favourite tool. Commonplace problems tend to fit snugly into spreadsheet-like models and behaviours. When confronted by a new problem, I invariably make tables to make sense of it. And I've used spreadsheets a lot in off-label ways too (Ever created dynamic data-driven app mock-ups in Excel?). Yet, it took some doing before I finally saw that I can (should) use the web browser + DOM as a dynamic medium to play with rather than an inert target to overwrite.

How it began: The DOM as a data structure

Text art was arranged in terms of 2D matrices (Javascript array-of-arrays). That was translated to HTML with which to replace DOM contents entirely, viz. artcontext.append(htmlizeArtSheet(art_sheet)), as seen here:

Treating the browser as an inert target.

function updateDom(

artcontext = document.querySelector('.textart'),

max_cols = MAX_COLS,

max_rows = MAX_ROWS) {

// with reference to ./tapestry_test.html

// This represents a flame animation sequence spread over 41 frames.

const flame_ddw_animation = ddwChars(candleFlameAnimatedDDW);

// Just pulling out arbitrary shapes of the flame, to place over

// each candle position.

const nine_flames = ["0", "1", "2", "3", "5", "8", "13", "21", "34"]

.reduce(

function (flame_frames, frame_id, idx) {

flame_frames[idx] = flame_ddw_animation.filter(char => char.frame == frame_id);

return flame_frames;

},

[]);

// Offset each flame data to coordinates that place each flame over

// each candle's wick.

const nine_flames_transposed = [{x: 3, y: 2}, {x: 11, y: 2}, {x: 20, y: 2},

{x: 29, y: 2}, {x: 39, y: 2}, {x: 48, y: 2},

{x: 57, y: 2}, {x: 66, y: 2}, {x: 75, y: 2}

].flatMap(({x, y}, idx) => transposeCharLocations(x, y, nine_flames[idx]));

// Composite teaserDDW data with overlay data of the nine flames.

const teaser_with_flame_ddw = ddwChars(teaserDDW).concat(nine_flames_transposed);

// Reshape the composite data into the expected matrix form that will be painted.

const art_sheet = insertDdwCharsIntoTextArtSheet(teaser_with_flame_ddw, max_cols, max_rows);

// console.log(art_sheet);

// Finally... Paint the text art!

artcontext.append(htmlizeArtSheet(art_sheet));

return artcontext;

};

The workhorse function was a Javascript matrix manipulator:

function insertDdwCharsIntoTextArtSheet(

ddw_char_array,

x_cols = MAX_COLS,

y_rows = MAX_ROWS,

ddw_char_maker = makeDdwChar) {

const insertIfPositionExists = (char_matrix, ddw_char) => {

let {x, y} = ddw_char;

if (y < y_rows && x < x_cols) {

char_matrix[y][x] = ddw_char;

}

return char_matrix;

};

return ddw_char_array

.reduce(insertIfPositionExists,

makeTextArtSheet(x_cols, y_rows, ddw_char_maker));

}

function makeTextArtSheet(

x_cols = MAX_COLS,

y_rows = MAX_ROWS,

ddw_char_maker = makeDdwChar) {

return Array.from({length: y_rows},

(_, y) => Array.from({length: x_cols},

(_, x) => ddw_char_maker(x, y)));

}Yes, I didn't pay_attention to namingConventions in that version.

How it is: The DOM as a live spreadsheet

Now, everything is designed around a live "canvas" written to the DOM. Mechanically, the canvas is a rectangular grid of empty <span> elements, organised by and uniquely addressable by x/y coordinates set as data attributes. All text art operations assume the DOM already contains this live "canvas", and query/update any part of it, based on information set in the source data (coordinates, glyph, style, frames, tags etc.).

Treating the browser as a live medium.

function updateDom() {

let now = Date.now();

let han5738_begins = Date.UTC(2022, 11, 18, 16, 0, 0, 0);

let han5738_ends = Date.UTC(2022, 11, 26, 16, 0, 0, 0);

let dayZero = now > han5738_ends ? getStartTime(0) : han5738_begins; // depending on when a player starts the game

let todayNum = Math.floor((now - dayZero)/(24*3600*1000) + 1);

//////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Initialise the Text Art "canvas".

//////////////////////////////////////////////////

stopAllLiveAnimations();

paintEmptyCanvas();

// Parts of the Menorah to always show

let allMenorahChars = getDdwChars(menorahDDW);

let selectedMenorahChars = allMenorahChars.filter((char) =>

(char.tags.length == 0 || char.tags.includes("day0") || char.tags.includes("menorah")) &&

(!char.frame || char.frame == "off"));

let setOfFlames = new Set();

let selectedTapestryChars = [];

// Gather data to paint based on day and answers

for (let i=0; i < 9; ++i) {

// Flames to light up for any answered puzzle

if (isLit(i)) {

setOfFlames.add(i);

}

let toggleState = isLit(i) ? "on" : "off";

let dayTag = `day${i}`;

// Candle data for "today" OR for any already-answered puzzle

if (canBeLit(i) || isLit(i)) {

selectedMenorahChars = selectedMenorahChars.concat(

allMenorahChars.filter((char) => {

return char.tags.includes(dayTag) && (!char.frame || char.frame == toggleState);

})

);

}

// "Revealed" Tapestry data for any answered puzzle

selectedTapestryChars = selectedTapestryChars

.concat(allTapestryChars.filter((char) =>

char.frame == toggleState && char.tags.includes(dayTag)));

}

//////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Paint the art

//////////////////////////////////////////////////

paintTextArtPiece(selectedTapestryChars);

paintTextArtPiece(selectedMenorahChars, 19, 30); // offset by x=19, y=30 w.r.t. origin

// Light flames

for (const flameNum of setOfFlames) {

animateFlame(flameNum);

}

// Twitch Animals

[null, // candle 0, no animal for Shamash

beehiveDdwChars, // candle 1

snailDdwChars, // candle 2

spiderDdwChars, // candle 3

hornedOwlDdwChars, // candle 4

koalaDdwChars, // candle 5

squirrelDdwChars, // candle 6

toucanDdwChars, // candle 7

snakeDdwChars // candle 8

].forEach((animalDdwChars, candleNum) => {

if (animalDdwChars && isLit(candleNum)) {

twitchAnimal(

animalDdwChars.filter((char) => char.frame == "on"),

animalDdwChars.filter((char) => char.frame == "on2")

);

}

});

};

So, an empty "cell" like this <span data-x="30" data-y="42"></span> may get DarkDraw character information like this <span data-x="30" data-y="42" class=" fg255 bold" data-frame="off">)</span>. Where the source DarkDraw character data itself would look like this: {"x": 30, "y": 42, "text": ")", "color": "225 bold", "tags": [], "group": "", "frame": ""}.

Like this:

function paintTextArtPiece(

ddwCharArray,

xCanvasOffset = 0, yCanvasOffset = 0,

canvasContext = document.getElementById("art")) {

for (const char of ddwCharArray) {

el = canvasContext.querySelector(

`${EL_CELL}[data-y='${char.y + yCanvasOffset}'][data-x='${char.x + xCanvasOffset}']`

);

if(el) {

el.className = getCssForDdwColorStr(char.color);

el.dataset.frame = char.frame? char.frame : "";

el.innerHTML = char.href?

`<a href="${char.href}" style="color:#FFFFFF; font-weight: bold;">${char.text}</a>`

: `${char.text}`;

}

}

}What transpired in-between: Learning to "see"

Picture a reticent server-inhabiter bobbing about in a primordial DOM-soup, waiting for the stars to rise.

There is a knowing how to swim versus a knowing how to swim in the open sea. The raw skills are similar, but oceans are so very different from familiar swimming pools, that one has to learn a whole other way of sensing, observing, thinking, and operating. That is how it goes, in unfamiliar territory.

The slow star-dawn was the very process of relocating the "spreadsheet" from being in-memory (a 2D Matrix), to being an in-DOM grid of live elements. That in turn meant identifying the various parts at my disposal, and working out how to organise the solution using the pieces, viz.

design of raw data; its shape and structure,

{"x": 76, "y": 5, "text": "\u0194", "color": "88", "tags": ["wick", "day1"], "group": "", "frame": "on", "href": "1"}data transformation operations (filtering, enriching, reshaping)

const flameAnimationSequence = getDdwFrames(flameDDW) .sort((fa, fb) => fb.id > fa.id) .map((frame) => flameAnimationCharacters .filter((char) => char.frame == `${frame.id}`)) .map((flameChars) => frameInsideMask(flameChars, 3, 3));domain abstractions (canvas, text art pieces, painter, animator)

function paintEmptyCanvas( canvasContext = document.getElementById("art") ) {...}; function paintTextArtPiece( ddwCharArray, xCanvasOffset = 0, yCanvasOffset = 0, canvasContext = document.getElementById("art") ) {...}; function paintFlame( dayIndex = 0, frameCounter = new FrameCounter(41) ) {...}; function animateFlame(dayIndex = 0) { let animationID = setInterval(paintFlame, 100, dayIndex, new FrameCounter(41)); LIVE_ANIMATIONS_IDS_SET.add(animationID); };HTML/CSS construction (e.g. make a canvas of rows and colums, with data attributes set)

<span data-x="30" data-y="42" class="fg255 bold" data-frame="off">)</span>actual DOM manipulations (e.g. select/update element by data attributes)

canvasContext.querySelector( `${EL_CELL}[data-y='${char.y + yCanvasOffset}'][data-x='${char.x + xCanvasOffset}']` );

And so forth…

Ultimately, I suppose I retained the general data munging needed to prepare source data for writes into the DOM, and dropped the sort-of DarkDraw-to-HTML "compiler" piece from the solution. That piece was causing avoidable data munging work and was tempting me into over-abstracting code.

The revised approach also resulted in code that is true to the aesthetic feel of Text Art animation, which was the real win.

Details details details

The aesthetic of Text Art and its Animation

Characters are material; where a character is a glyph along with its associated information, including styles (256 bit colour palette), x/y grid position, order of appearance (frame number), tags, grouping etc.

Animation is discrete, not smooth; effected by replacing characters with characters.

Painting is not an emulation of the artist's intent, but a faithful reproduction of their hand, regardless of medium.

Our mechanical text artist was code in the web browser medium. But one can imagine implementing text artistry with stop-motion photography, or printed flip-books, or kaleidoscopes, or this wicked cool Dynamic Shape Display at MIT Media Lab.

Hark back to my note on thinking in terms of dynamic media.

Structuring DarkDraw source data

If the data sucks, the code will suck. Now there's a maxim for you.

I try to structure, fix, and enrich source data as much as humanly possible. If the data is well-formed and models the problem domain well, the solution domain (i.e. the code / system design) almost writes itself.

And when the resident artist quips thusly, it's pure gold.

"that's what's so fun about dd

it's all just data :)"— dwimmer

(dd = DarkDraw)

So, these became goals for the code:

- Construct a spreadsheet with x/y coordinates

- Place characters precisely into the appropriate coordinates

- Animate characters based on what they represent (flame, animal, etc.)

Over a handful of iterations of data modeling, our data representation came to have two types of records, as follows:

"Frame" records that contain information about a single frame.

{"id": "off", "type": "frame", "text": "", "color": "", "tags": [], "group": "", "duration_ms": 100}These come bundled in a

ddwdata file. VisiData uses these to render DarkDraw text art animations. Our game requires only two kinds of animations: flames that cycle over 42 frames, and animals that blink (on/off frames). So I just wrote special functions for each kind of frame-handling. A general frame-aware animator is TBD. Maybe next year :)"Character" records, which we tagged semantically. Is it for a squirrel? A wick? The menorah? Which day of game play to associate it with?

{"x": 76, "y": 5, "text": "\u0194", "color": "88", "tags": ["wick", "day1"], "group": "", "frame": "on", "href": "1"}Given this, our Javascript can interpret each character record to decide whether to place it in the DOM (Is it the right day? What is the frame state?). Then, to place it, we locate a cell for the x/y coordinates, punch in the text, add appropriate CSS class for the color value, and link the cell if an href is specified.

Choice of Javascript

It's just Javascript.

The good parts.

That's all.

Choice of animation method

Even "just" Javascript provides us several options: setInterval, setTimeout, Element.animate, Window.requestAnimationFrame, to name a few 5. CSS adds more to the mix. However, Text Art Animation aesthetic asks us to work with characters as material, so CSS animation methods are out from the outset.

Window.requestAnimationFrame had me on the fence

It is supposed to be CPU friendly because it works with the browser's render cycle 6, and I have a feeling one can do a proper job of animation with it—unlike Element.animate discussed below. However, setInterval and setTimeout worked well enough that I didn't feel compelled to experiment more. A game had to ship, after all.

Element.animate is neato, but it cannot modify elements

Also it requires us to model discrete animation in terms of carefully-chosen keyframe effects. These traits combined imply we might emulate the artist's intent, at best. Thus it does not suit our purpose.

Element.animate() is not text art animation.

An unrelated but important detail, because of the unwelcome hair-loss it has caused me… Element.animate does not work visually for inline elements like <span> unless they receive block properties via CSS, viz. display: inline-block;.

Like if we document.getElementById(theID).animate({...}) an inline element (no block properties), then document.getElementById(theID).getAnimations() shows that an animation is indeed running. However nothing is visible in-browser.

So my guess is, unadulterated inline elements seem to behave like point objects as far as animate is concerned. This little detail seems to be conspicuously absent from MDN and StackOverflow combined. Unless I've misunderstood everything, of course.

This took way longer to debug than I'm able to admit in polite company.

setInterval and setTimeout worked just right

These let us call functions that do exactly the thing we want, viz. punch characters into our "live spreadsheet" medium, exactly the way the artist placed them in the original art source. These methods can make a CPU sing, but hey, the awesome art is worth every watt it, ah, draws.

setTimeout and recursion.

setInterval.

Composition and Painting

Graphics artists will find this section wholly unsurprising. Our Text Art is a composite of parts. These include:

- static parts like the base of the menorah, parts of the tapestry

- animated parts such as flames and twitchy animals

- "revealed" parts that could be static and/or animated

We can think of each part as an abstract sheet. Sheets of art are over-painted on a shared blank rectangular canvas of pre-set size. A sheet may be as small as one character, or as large as the whole canvas, and may be of any shape in-between.

All art is painted with respect to the same x/y origin, where the coordinates follow display screen layout:

- x = columns of a sheet of text art

- y = rows of a sheet of text art

- 0/0 origin begins at the top-left corner

For animated text art, sheets are associated with animation frames. We view this as a stack of text art sheets, one sheet per frame. Since it's all 2D space, we are sort of "looking from above" and can't see the depth of the stack. Frames are irrelevant for static text art; there is just one sheet.

Mechanically, our animation is quite like flipping a flipbook. A subtle detail is that animation art should explicitly paint blanks where it does not want to show characters. If source data contains explicit blanks, our code can blindly punch characters into the DOM. Otherwise, our code has to calculate empty cells, which creates needless complexity (for me it was that first version that I trashed).

Conclusion

Animating text art in the browser is a lot of fun… have at it! Draw with DarkDraw. Export as JSON. Drop some Vanilla ice ice baby Javascript. Profit?

Copyright notice

All Hanukkah of Data text art featured in this piece, in any form (e.g. screenshots, source data, rendered samples) are copyright dwimmer. Reproduced with permission. If you like the art (and why wouldn't you?), give him a shout out. Better still, commission him to make rad stuff for you!

Acknowledgments

Cheers to all the devottys for a super fun time making Hanukkah of Data. It was my first time working with an artist to render their work, and I'm glad it was someone like dwimmer. A joy! Thanks to Saul, Anja, Radhika for reviews and remarks on this post.