Reframe Technical Debt as Software Debt. Treat it like a AAA-rated CDO.

I've long struggled with the *Technical* Debt metaphor. It was immediately useful when I first heard it. I still think it is useful, albeit as a starting point. The more I worked with software, the more infuriatingly incomplete it started to feel. So I've reframed it as *Software* Debt, for myself. Here's what I'm thinking.

Contents

Backstory

Some years ago I found myself in a rabbit hole, researching the 2008 financial crisis. It reminded me of other insane stories like Knight Capital, and further back, about how Enron imploded (because Enron India's meltdown was shocking, and destructive. And because a dear friend, in his past life, was on the team at Lehman Bros. that structured financing for Enron India. So come 2008, when Lehman imploded, I got to hear about the hard-chargin' super-leveraged risk-takin' days from someone who was there in the early part of the so-called Dick Fuld era. It was all very fascinating, but I digress…).

Down in the rabbit hole, a slow realization began.

One source of my unease is that I think discussions of Technical Debt don't sufficiently examine the nature of the Risk of the underlying challenge. The other is that the concept skews and pigeonholes the Responsibility part of the underlying challenge.

Note: In this post, I have software organisations in mind, viz. ones that exist mainly because of the software they make and ship (whether priced or gratis).

Framing pigeonholes Responsibility.

I find the Technical part problematic because it is too narrow a context, and that narrow framing leads to real trouble in software orgs.

It inadvertently paints a small set of people as the "owners" of the "debt", which is not untrue, but it is incomplete, and the framing by its construction inadvertently places the rest of the organisation in the role of creditor. The framing further pigeonholes our thinking about risk, and causes us to set up adversarial objectives and communication structures among the organisation's many functions and layers.

Narrow framing is bad because software orgs–especially fast growing ones–are always in a state of churn, conflict internally and with the outside world, and a state of partial failure. Because a running, live software system is as much a fermenting vat full of culture, opinion, future-thinky bets with people constantly dipping in for a taste, as it is bit-flippin' transistors mindlessly following truth tables.

We have since invented other terms like "organisational" debt to prod people to think more holistically. I prefer to say "software debt", and mean it to apply to the whole of any given software organisation, because of how I have come to think of the debt bit of software things (and org things in general).

Sadly, narrow framing abounds, and we end up producing malfunctioning software organisations far too frequently.

And so, far too many learn what it feels like to try and get the big bank to refinance that home loan when the world suddenly became hostile to them, and they were too little, too alone, and too powerless to engineer a central government bail out. The best they (we) can do is to vote for a government that hopefully reforms policy and simplifies tax regimes and does generally smart stuff such that more people come out of poverty, fewer sink back into it, and more people achieve prosperity. Become a "Generative" type of org, in terms of Westrum's typology of organisational cultures.

At the same time, personal responsibility is not waived away. The least we (they) can do is to not be foolish in the first place. Resist those easy temptations. Not bite chunks we can't chew. Not eat what we can't digest.

Say No To (Software) Debts.

Software debt packages risk. We need better mental models of that risk.

Within the frame of "technical" debt, we frequently discuss the "debt" in terms of code quality (cleanliness, understandability, efficiency, maintainability), and architectural quality (the goodness of domain models, core abstractions, application boundaries and interfaces etc.).

This is a sort of human indebtedness, as in, are we being kind to each other, and helping each other be productive? Because if we are productive, then we will get more done with less effort (leverage), be able to ship more, faster (throughput), and respond to market needs more creatively (innovate).

These are undeniably important considerations. But…

- they are certainly not firewalled off from the rest of the organisation. For example, to a good first-order approximation, we tend to "ship our organisational structure".

- they are second-order outcomes of a more fundamental kind of thinking, viz. one about risks and associated trade-offs.

So I think it's worth framing a notion of Software Debt, to re-scope the discussion at an organisational level, and to find a better mental model of the risk packaged by the debt.

Software debt risk perception is muddied by personal bias.

Part of my unease, and I suspect yours, stems from how the idea of debt is anchored in our heads.

We struggle with this bias when pricing things. We sell to our wallet. If we are used to buying most things for 10 tokens, we balk at the idea that someone else is fine charging 100 tokens for basically the same things, and that others are fine—delighted, even—to fork over the requested quantity of tokens.

Likewise, the word "debt" is strongly anchored to a personal sense of financial debt; our credit loan cards, home loans, equated monthly installments. Small, familiar ideas. Safe-sounding numbers. A warm feeling absorbed and internalised through delightfully tempting messages of better lives, buttressed by the approval of friends and family when we get that car or house or desirable object.

Given the sheer amount of personal financial debt, our frequency of involvement with it, and the normalisation of it being fine to always be indebted to one or more financiers, I suspect this anchoring bias is widespread. And it clouds our risk perception when thinking about software debt.

Software debt is rooted in complexity. We abhor complexity.

Complexity is to software what mass is to a rocket; the hard limiting factor of growth in any dimension you choose to measure (shipping velocity, headcount, revenue, cash flow, account expansion; anything). This is the sort of thing that demands tree-recursive, networked thinking we are not good at doing explicitly and deliberately. Something that our education actively disables by drilling us to think in simplistic linear terms in which correlation amounts to causation.

So much so that we have a visceral negative reaction to the self-control and effort needed to think hard, think deep, and think persistently with focus, constantly refining, testing, challenging, updating our mental models of reality. You just had a visceral negative reaction simply by reading this description, didn't you?

Software debt is inevitable.

Complexity is inevitable. Thus risk is inevitable. Thus debt is inevitable.

Like rocket mass, the more we scale it, the more we pack in, and the more we make it do, the more complexity we accrue. But also like rocket mass, we want some kinds of complexity; the kind that is at the heart of wherever it is that we aim to go. That is, we want to take on essential risks, but ruthlessly reject non-essential risks.

This is not easy at all, but it is a critical function of people making software, especially because it is so easy to create complexity. Put a network between two single-core computers, and boom, you just made a distributed system fraught with undecidable problems. Add mutable state to your program, and boom, now you have to also remember the past to make sense of the present. Add an extra CPU thread to your two computers and you have a stateful concurrent/parallel networked system on you hands. And now you have to think in non-sequential time about distributed problems with multiple pasts and multiple futures.

Most of us don't have to, because we benefit–often unwittingly–from very generous error budgets and low-impact risks. But make no mistake, someone had to, and someone did, which is why you and I can ride the coattails of risk curves all our lives and be paid handsomely for their troubles.

Software debt always compounds.

In simple terms, all debt reduces down to three key components: A principal amount, a rate of interest, and terms of payment (including repayment period, cadence etc.). The combination of interest and terms price the risk for both parties.

In software terms, we may think of each piece of tech in the stack as raw mass, adding to the principal amount. The more we add, the more we risk, even if the rate of interest remains constant. But really, each decision to add or remove items from any part of the system changes the principal and the rate of interest and the repayment terms.

This alone should cause sleepless nights. Compounding debt grows and grows. Slowly, creepingly at first, and then very fast. And suddenly you lose everything.

Software debt is layered.

Because software parts compose into software "stacks" and hierarchies, and each part mutates/evolves up and down the towers.

Say we only ever have a fixed set of software parts–say one kind of server-side application, backed by one kind of database, serving one kind of client, via one kind of server, on one kind of operating system. Sooner or later, each part is guaranteed to update in-place, and/or do more work, thus forcing a change in their operating environment.

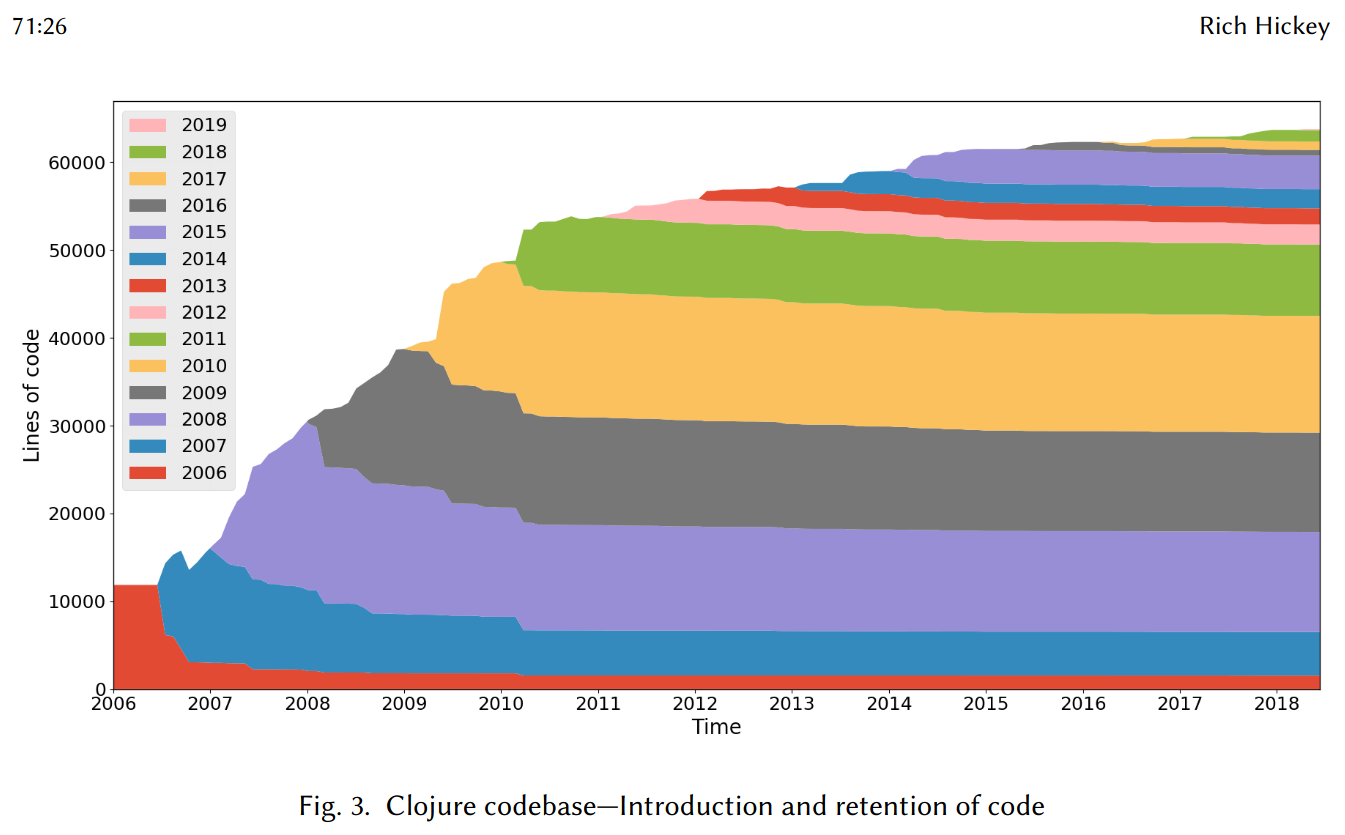

The database gets more data. The application handles more edge cases. The server balances more concurrent load. The OS gets security patches. The clients want to do more so everything accrues more features. On and on, mutating forever, exhibiting accretion, sedimentation, erosion, and tectonic upheavals. Not to mention the parallel layers of brains of the people making decisions about these things; the Top Dog, the Fresh Recruit, and the squishy organisational cake between those two.

See also: The half-life of code & the Ship of Theseus

Software debt is networked.

Because software itself is networked, even inside applications. There are call graphs, object hierarchies, and effects-at-a-distance. These often interact in ways that surprise us. Small local changes can turn into literal chain reactions of events that have stunningly large impacts on the state of the physical world we walk in. The meltdown of Knight Capital stands out starkly as an example of unmitigated, un-hedged software debt.

It goes way beyond in-app networks, of course, because we have come to depend on global software supply chains. These are quite unlike logistical supply chains, as:

- they demand almost no capital to participate as creator and/or as consumer,

- they place no barrier on becoming a critical node (aheam, left-pad), and

- they afford no reaction time when things go bad. Failures and compromises affect the world near-instantaneously, at the speed information travels.

It's insane that we have become habituated to the idea that adding a single library to one's project can pull in tens or even hundreds of transitive dependencies, and that's fine.

I'm writing this in the wake of the aftermath of the disclosure of the log4j zero-day vulnerability. But this is only a recent example of just one kind of networked risk.

With managed services we effectively add one more level to the Inception world of our software organisation. We outsource nice big chunks of supply chain risk management, but we in-source a different risk of depending critically on entities that we do not control and cannot fix if they fail.

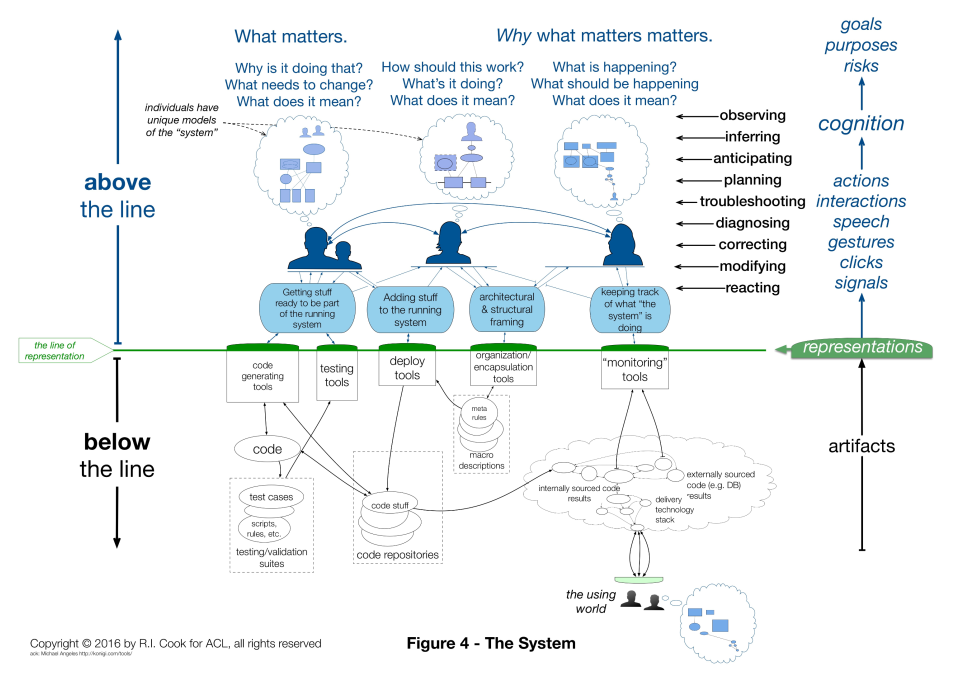

Not to mention the fact that change ripples through the parallel yet deeply enmeshed dimensions of cyberspace and meatspace. Code running on hardware is inexorably tied to concepts running in wetware. Of course, at this level of abstraction, the notion applies to any field of human endeavour. Yet, it is so much more true of software. Because software is essentially the thoughts of people being played on repeat.

See also: the Stella Report found via John Allspaw's How Your Systems Keep Running Day After Day.

Software debt is like a complex opaque financial derivative.

To me, unchecked creation of software debt is exactly analogous to how the 2008 financial crisis came to be. It was wrought of "simple" debt packaged and repackage in inscrutable derivative ways, stacked into towers of debt, where the aggregate collateral backing it looked sound, but which actually had very shaky foundations, that the abstraction obscured. The crazy thing is, the trouble at the bottom was apparently sitting around in plain sight, to terrify anybody who cared to literally walk over and look at it. The current state of our software supply chains look uncomfortably similar, for example.

But as it happens, growth forgives all sins. We fall in love with the thrill. We fail to stay a little paranoid. Our position becomes increasingly leveraged. The tail risks compound (demand swings, malicious actors, regulatory change, supply chain exposure, …), and so do the odds of any one of those risks exploding in our faces.

Our system, as in, the integrated networked whole of compute infrastructure, managed services, libraries, product management, design, operations, sales, marketing, org strategy start looking like piles of debt obligations. Each represents part of a promise made to the outside world, and here's the kicker; our rate of growth is collateral. Small deceleration of growth rates magnify into large percentage drops of "valuation" (however it is measured). Since bad news travels farther and faster than good news, the negative bias tends to be stronger. We seldom gain value as much, or as quickly, as we devalue.

So, if we are not ruthlessly pragmatic and strategic about software debt, you and I will keep accruing the bad risk kind of debt. One day, at the least convenient time, the world will come a-calling, demanding what we owe. And if we can't cough it up, it will take everything away. All moments are least convenient when that happens.

Much as I dislike all this doom-speak, I have to acknowledge it is material, and to side with Andy Grove. Only the paranoid survive.

The only real hedge we have is the creativity and intelligence of our people.

1,000 words in 1 picture: xkcd summarizes it best.

Stories of Debt and Destruction

- A list of Post-mortems curated by Dan Luu, Nat Welch and others.

- A list of "Events that have the dark debt signature", in the aforementioned "Stella report".

- Knight Capital, August 2012

- AWS, October 2012

- Medstar, April 2015

- NYSE, July 2015

- UAL, July 2015

- Facebook, September 2015

- GitHub, January 2016

- Southwest Airlines, July 2016

- Delta, August 2016

- SSP Pure broking, August 2016